Photo by Marie Yako

With 13,000 asylum seekers still living in emergency shelters in Berlin, refugee housing might not be a popular topic, but it’s a pressing issue. While artists and architects don’t lack ideas, the city government has so far opted for short-sighted solutions. Can’t we do better?

A few hundred metres away from S-Bhf Ahrensfelde, in the heart of Marzahn Plattenbau land, two nondescript concrete blocks appear behind construction fences and yellow excavators. At five storeys, they are not tall enough to dwarf the nearby high-rises. Square, grey and crude, they look like office buildings – until you notice the children on the playground. A permanent fence and some barren soil waiting to be seeded with grass separate them from the street. The inside is similarly dull and sterile, its narrow rooms resembling a bare-bones youth hostel. A new generation of prefab homes in former GDR territory?

This is actually refugee housing – the latest devised by the city of Berlin to shelter its 35,000 asylum seekers, on top of those 100,000 refugees who were already granted temorary stay. An upgrade from short-term “Tempohomes”, MUFs, or “modular accommodation for refugees”, are a more durable option supposed to house asylum seekers for up to 30 years. The MUF at Wittenberger Straße 16-18 was the first of 10 identical blocks housing 450 people each to be constructed by Berlin’s department of housing and urban development. It was put to use in January of this year and now has two brethren, one in Marzahn and another in Reinickendorf.

A one-storey administrative building houses a gatekeeper, fire alarm centre, doctor’s office, laundry room, common room and staff rooms. The two dormitories are made up of three 18.5mx18.5m modules, assembled from 3x6m prefab concrete slabs within 47 weeks. The five-storey modules contain a combination of small flats and single and double bedrooms housing 15 people per storey; each floor also has two windowless bathrooms and a common area including a kitchen.

It’s drab and generic, but surely it must have been cheap? Well, no. This MUF cost €17.8 million to build, or €1470 per square metre – more expensive than regular permanent housing, remarks Christine Edmaier, president of Berlin’s architecture association. She laments the city government’s tendency to order the construction of refugee housing without consulting any architects. “Modular building techniques, whether containers or Platten, are not the issue. Both could be appropriate if they were planned out right – for example, making residents’ privacy a priority.”

For Edmaier, the main drawback with the MUF is that they are not a sustainable solution. The Berlin government or Senat has stated the MUFs are meant to be used for 50-100 years, explaining that once the refugees are gone, they can eventually be re-purposed as student or senior housing, or even turned into proper apartments.“This isn’t very realistic. There will always be new refugees coming to Germany, and we don’t want to put them into hostels or school gyms. So we will always need a certain number of accommodations for newcomers.” She believes better solutions were found in other German states, Bremen for example: “They are engaged in building proper permanent housing. Unfortunately, there have been no efforts to do something comparable in Berlin.”

The Senat seemed briefly to care about creativity when building director Regula Lüscher launched the refugee housing architecture competition “Berlin Award 2016 – Heimat in der Fremde”. Winners were accepted to the 2016 Biennale. Many of the projects proposed integrative solutions – like one of the winners, Raumlabor’s concept for Haus der Statistik at Alexanderplatz: refugee housing alongside co-working spaces for art, culture and education in the abandoned building. Others suggested communal living quarters in which refugees would live with students or homeless people.

What happened to these winning projects? Though some are now being privately funded, the city has put no money towards any of them. “Mrs. Lüscher’s competition was nice, but what we need are suitable plans for each individual site,” says Edmaier. “There are enough ideas around, and many good examples in Germany, but no financial or human resources allocated to executing these projects,” says Edmaier. Even in March 2016, her organisation criticised the Berlin Award, calling it “somewhat cynical and hardly sufficient in the current situation”.

For Sascha Langenbach, spokesman for Berlin’s refugee administration agency (LAF, formerly known as LaGeSo), it’s not so much the money that’s lacking but support among both politicians and society. “Building new refugee housing is not a popular topic. It doesn’t matter what you want to build or how you want to build it. Even in Kreuzberg, where people walk around with ‘Refugees Welcome’ on their shirts, you’ll hear, ‘We don’t have anything against refugees, but this building does not fit in here.’ We’re still worrying about the basics: finding a roof for each individual. So we won’t be talking about art anytime soon.”

He’s right, but only partially: one to two percent of state funding for any building project is allocated to artworks, and refugee homes are no exception. A call for artistic interventions by the Wiechers Beck society of architects for the 10 planned MUFs is currently in the works, and winners will be published near the end of June. So at least that drab housing block on Wittenberger Straße will be getting a bit of colour.

Where are they now?

The last school gym might have been evacuated at the end of March, but according to LAF spokesperson Sascha Langenbach, between 12,000-13,000 asylum seekers still live in emergency shelters, many of which lack appropriate sanitary facilities, not to mention privacy. Tempelhof airport is only the second largest of these after the Schmidt- Knobelsdorf-Kaserne, an old army base in Spandau which currently houses around 1000.

Pressed to come up with solutions, the city of Berlin devised a short-term housing plan: “Tempohomes” (photo), container villages consisting of 64 shed-like modules housing a total of 200 residents per settlement. Five of the planned 10 Tempohome sites are already in use. But they’re a short-term, rudimentary solution – devised for just three years, housing mostly single men because of their cramped conditions’ lack of privacy.

The prefab housing blocks known as MUFs (modular accommodations) were conceived as the next best solution. Three have been built and are already in use so far, housing a total 1160 people. Another 23 are in the works for 2017. All in all, Berlin should be the site of 30 Tempohomes and 60 MUFs by 2021. But their large size and the difficulty reconverting them at the end of their lifespan mean that many districts are fighting their construction.

———————————————————————————————————-

Housing refugees creatively

In addition to the winners of the Berlin Senat’s competition, here are some other refugee housing solutions Germans have dreamed up:

Over the rainbow—Queer counselling organisation Schwulenberatung Berlin, in cooperation with Christoph Wagner Architects and Wenke Schladitz, is planning a new house near Ostkreuz for 32 LGBTQ inhabitants, refugees and seniors alike. It should be completed by the beginning of 2018.

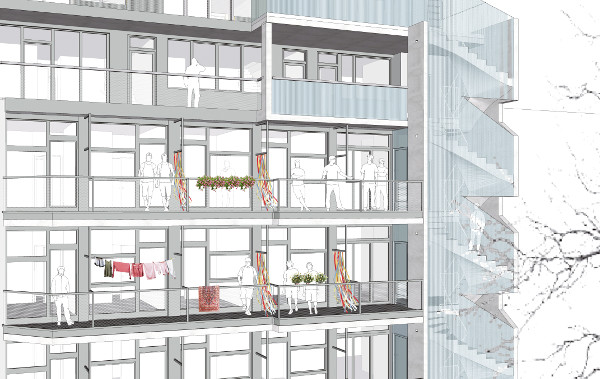

Put a cube on it—The studio Architekten Kauschke + Partner proposed to set modular cubes with refugee housing on top of the existing buildings at Wilhelmsruher Damm 81-91 in Reinickendorf. The proposal has yet to be picked up by investors.

Taking over—Jörg Friedrich, a professor at Hanover’s Leibniz University, had students design new concepts for refugee accommodation, re-purposing unused spaces such as floating barges, parking lots and community gardens or Schrebergärten for shared space and integration – though for now, these remain mere concepts.

Build it yourself—In Tübingen, Studio Schwitalla and Danner Yildiz Architekten designed the “Tübinger Regal” project: a concrete ‘shelf’ with clay walls built by the intended 40 refugee and 10 student inhabitants. Its intended completion is 2018.