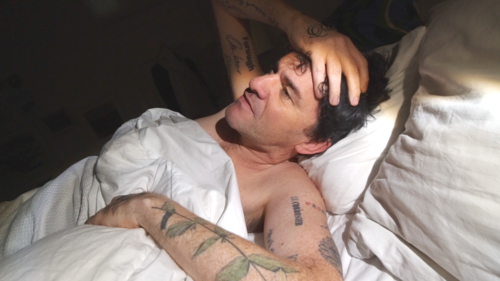

Mark Cousins initially began working on The Story of Looking as a film version of his eponymous 2017 bestseller, which explored how people view and interpret what they see. The project was threatened first by funding and then, ironically, by Cousins’ own eyesight. After being diagnosed with cataracts, the project refocused: Cousins decided to film his operation and recovery, starting with the image of himself in bed. The resulting film is an investigation of the eye in its endless permutations – from small, sensory organ to creative powerhouse tool.

Your film is a celebration of looking. We were wondering if there was anything you wish you hadn’t seen?

Yes. I’ve seen dead bodies, I’ve worked in war zones. I was in Sarajevo during the siege, and I was in Iraq during the war. It’s troubling to see. But for us, as citizens, we have a duty to look at the worst, to not be naive or sheltered from moral and political implications. I will look at the worst stuff I need to see. I haven’t sheltered myself.

Especially as we have the privilege of being able to see. I remember a programme you curated at the British Film Institute that included The Unseen, the Czech documentary about blind children photographing their surroundings…

I had a producer once, when I was making The Story of Film, who said, “Tell me what you see.” That was brilliant.

In The Story of Looking, you use Twitter to ask questions and record yourself reacting to them in real time. Did getting those live tweets change the process?

In some ways. It’s one of the things we know as writers and filmmakers, that what we’re trying to do is look for aliveness and to make our work alive. And when I did that with the tweets, I wanted to inject energy.

What we’re trying to do is look for aliveness and to make our work alive.

The film premiered two years ago now. How is your eye doing?

Good. I mean, the operation was fantastic – I can see clearly, but there are intrusions, and the brain has to listen to those intrusions… I think there’s probably a metaphor in there somewhere. What you don’t see in the film are my conversations with Christopher Doyle, Wong Kar-Wai’s cinematographer. He and I have done films together, and he’s also had a cataract. He told me that since his cataract operation, he tends to find yellow in some of those films.

Would you have made the film in the same way if you weren’t having the eye surgery at this specific time?

I haven’t been asked that before. I’m interested in architecture, and the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier said that technology is aesthetic. So this film is very influenced by minimal technology and shooting on a small camera. Everything came from that. I could have done a different film with more technology, with tracking shots and stuff like that. But you make the best with what’s available.

How do you start an undertaking as big as The Story of Looking?

Well I wrote a book on the same theme first. I was looking at the aspects of visuals. I could see when I looked at a film or painting, it was as if I was lifting its hood and seeing the engine… but to answer your question, I kind of sketched out the structure.

Were there any limitations to the project?

The visual world is a big subject, and in the past I’ve done some very big films – 15 hour films. But we couldn’t get any funding for that. So I thought: let’s radically repurpose this. I wasn’t going to tour the world with this film. So it became the absolute opposite – something to create in my bedroom, radically personal. That was the only way of turning it into something of integrity.

How did you find the experience of making The Story of Looking?

Overall, it was a good experience, and I was on safe ground in a way. There’s always the question of how to avoid banality. How do you avoid not saying the obvious thing – regardless of whether you’ve got a budget of €5 million or a shoestring budget. This isn’t the first time that I’ve made an artisanal film. In each case I think, okay, there’s a challenge of coming across as narcissistic. How do you make a film that is about yourself but open it up to touch an audience? Everybody today wants to tell their story. It’s easier said than done.

How do you make a film that is about yourself but open it up to touch an audience?

What influenced your approach to working in film?

I’m influenced by my working-class background. It can feel like a world where there’s an invisible exclusion zone. But from this working-class background comes a warmth and passion. I’m lucky to be friends with Irvine Welsh, and he and I talk about this a lot. How do we get to the point where we can do what we do? We want to make sure that there’s a warmth about what we do.

Do you yourself feel there are glass ceilings?

Yes. It’s a complicated thing. When I started, people were judged by looks. I looked younger than I was, and I recall – and I will not name names here – attending a Scottish film industry event and leaving that night crying on the train home because I felt nobody talked to me. Nobody was welcoming. No one is being explicit, but there are undercurrent codes and messages. I was excluded from my own event.

On the flipside, I know people are surprised by my warmth when they meet me – and I’m lucky enough to have met many great filmmakers. Funnily enough, do you know the British comedian Michael McIntyre? He published a memoir, and people asked if I’d read it. I said, no. It tells a story from when I was director of the Edinburgh Film Festival many moons ago. He came up to me as a student and describes how incredibly nice and helpful I was to him.

What were your formative cinematic experiences?

I’ve worked with Tilda Swinton over the years, and we can both recall the moment when we became aware that cinema was a powerful thing. That moment for me was watching Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Yes, it was a horror movie. I was scared. But I also became aware of cinema’s form. These were some of the most important moments. I became so hungry for cinema – I just became a sponge.

Sometimes you find that some of the best cinema is on your doorstep. Scotland has some real cult figures…

Ah yeah, I mean, Bill Douglas! Years ago I said to the Scottish Government, if you’re going somewhere, seeing foreign delegations, bringing gifts like whisky and haggis… why not bring Bill Douglas! But his difficult and dark films have connotations. Even today people say his work is ‘nasty’ and ‘negative’. Of course, back then it was even worse – but for me, his Childhood Trilogy is one of the best things in the history of cinema. But still, it’s not in the annals.

And of course, as an Edinburgh man yourself – Margaret Tait!

Actually funny story, don’t know if you know this, but in Scotland we have blue plaques we dedicate to famous people, historical characters. So we decided to try to get one here in Edinburgh for Margaret Tait. But it couldn’t get through or be accepted. So we just made it by sticking one up ourselves (laughs). Our place for her, you know? And then we stuck another one just by Waverley Station a few years ago. And they’re still there.

And then from Glasgow, there’s some real hidden gems – Peter Mullan’s Orphans is a masterpiece.

You know a funny thing? We’re talking about all these Scottish films, but one of the best Scottish films ever made has got to be I know where I’m going!, which is made by a Hungarian and an Englishman. I think that this is actually kind of our story. And it’s a good thing.

Have certain theses – or themes – followed you, as preoccupations throughout your work?

If anybody looks at my work, there are certain things: childhood has been a key thing. Of course, feminism has also been a big thing for me.

Walking helps me relate to places. I have actually walked across Berlin three times.

Also, I’ve mentioned that architecture and walking have been important for me in different ways. Walking helps me relate to places. I have actually walked across Berlin three times. I’ve walked around Moscow and across Beijing, Shanghai, Tehran. You find yourself asking, why do these things reappear, and what are the reasons? I think I’ve noticed more and more that people who go on really, really big walks are often quite anxious. I’m getting a bunch of lifetime achievement awards around the world, and in each case I try to build in a couple of days where I don’t have to do anything. I like to go for a walk around the city and shake off the anxiety.

Do you feel that cinematic images have lost their potency as a medium? Images are everywhere as part of modern culture, we’re flooded with an overload of disposable images. Take TikTok…

I suspect that if you were in Babylon, or the Middle Ages, or if you were in Rome in its heyday, you would feel bombarded by visual standards and feel a sensory overload. So I wonder how new this question is? It’s always been the question about how we absorb imagery. But you know, is that really true? Have you read Walter Benjamin’s writings about visual stimuli – and Hume, who was writing in the 1700s.

Does this perspective still apply, though? Nowadays, in this culture, the vast amount of people don’t even have the time to look…

When you look at those writers, you can generalise, but if you look at the Netflix-style of documentary filmmaking or filmmaking in general, there seems to be a distrust of the image. People watch fifty-hour box sets, you know, and routinely binge through five hours a night. Stuff like that. So again, I’m often suspicious of the received opinion.

Back to The Story of Looking. We both found the third act surprising. Could you elaborate on what brought about such an ending?

Well, there were a few things going on, but fundamentally it’s a film about aging. I was also considering how at times certain films lose themselves and their audiences and taper off towards the middle. When it comes to the ending of a film, there’s a real danger that the best moment in your film is about that 50-minute mark or the 60-minute mark. And I know a lot of the critics didn’t totally love the third act of this film.

Fundamentally it’s a film about aging.

You said your film is a reflection of aging. Do you feel like you’re slowing down or refining?

I haven’t said this in public yet, but I’m embarking on a new project called The Story of Documentary Film. It’s going to be nice, because I don’t feel like slowing down. I think that imaginatively, I’m on the way up.

- The Story of Looking was released in German cinemas on Feb 5